Feb 18 2014

Bounded Carnival with Limitless Memory

The author, Padraic Kenney, argues that social and political movements changed the relationships between communist states and their populations in the years before 1989 in such a way that made possible the seemingly sudden revolution. He uses the term carnival to highlight the plural and joyful nature of many of the phenomena that constitute his subject matter. This argument differs somewhat from that presented by Gale Stokes in The Walls Came Tumbling Down in that his focus is narrower, on the 1980s and particularly the years between the 1986 incident at Chernobyl and 1989. It also highlights much more the role of grassroots dissent and its variety of political flavors and younger/smaller characters (Ludwig Melhorn in the GDR, Czechs like Jan Svoboda, Petr Placák , and Ruth Šomorová, and Hungarians like Tomás Fellegi and István Stumpf) rather than the well known opposition leaders (like Lech Wałęsa, Adam Michnik, Vaclav Havel, etc.) or party leaders (Károly Grósz, Imre Pozsgay, Gen. Jaruzelski, Erich Honecker, etc.) that dominated the narrative in our first reading.

The cast of characters and sampling of organizations presented a broader view of the people who participated in the carnival from 86-89. Kenney made the accounts much more vivid for having so much detailed personal recollection; and perhaps dealing with personalities of students and artists, among others, made it easier to flesh out the stories than those of the big names. Environmentalists, church activists, teenaged students, and varied musical devotees (of punk or John Lennon) changed the nature of dissent; by embracing causes that were not explicitly political to break the stranglehold of the communist party on various facets of life, they made things like music and school into political spheres and their resistance thus became political. Surrealist performers and artists, bringing the public on the street into their spectacular “happenings” found innovative ways to combat communist orthodoxy; not by “refusing to ape official ideology,” but instead they found it “more effective to ape it grotesquely” (1). Confronting party rhetoric in public gave another view of the hollow promise of communism which was publicly visible in an empty Warsaw butcher shop (2), but had not previously been open for public discussion.

Though some of the important groupings that provoked public action were supplanted by the older dissident leaders (as in Poland when Solidarity took the lead at the Roundtable negotiations), their efforts built momentum for a civil society that laid foundations for revolution and later political pluralism. Kenney uses extensive personal interviews, ranging from 1996 until 2000, while acknowledging that he accounts for personal biases by claiming to filter out obvious accounts of personal self-glorification or blame. He also lists a great number of samizdat publications as sources of direct evidence. Kenney concludes that the end of the carnival came suddenly in each case, but that the training needed to make it possible came over years; 10-13 in Poland, followed by progressively shorter courses in Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Czech lands, East Germany, and Western Ukraine. He mentions that many of the younger leaders were marginalized in favor of the Havels and Wałęsas once the negotiations began for new governments. Where Stokes moved from cautious optimism to a more circumspect reflection between his first and second edition, Kenney writes in between and seems to present the carnival as having ended firmly when the revolution came. His reflection is more about the memory of participants, and in the end how the lack of public catharsis manifests in a lack of public remembrance, than on the legacies that are observable in the societies of contemporary Central Europe.

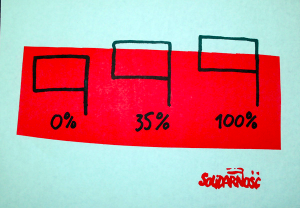

The Polish Voting Rights poster (3) seems a good representation of the way the old guard (of dissenters) harnessed public energy, preserved during the period of martial law by a flowering of different aboveground and underground groups, for new electoral possibilities. An electoral strategy to compel change in a new government (with a Senate as a new feature) relied on an empowered populace that had come to believe in change as a realistic prospect.

1 Kenney, Padraic. A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe 1989. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002. p.159

2 Chris Niedenthal, “The Butcher Shop, Warsaw,” Making the History of 1989, Item #23, http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/23 (accessed February 18 2014, 1:27 pm)

3 “Polish Voting Rights,” Making the History of 1989, Item #93, http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/93 (accessed February 18 2014, 1:27 pm)

Comments Off on Bounded Carnival with Limitless Memory